You’d think that synchronizing the clocks across a fleet of modern servers is a solved problem, but it’s actually quite a hard challenge to solve, especially if you want to get to nanosecond accuracy. This also means that it remains an axiom in computer science that you should never build a system based on clock time. Clockwork.io, which is announcing a $21 million Series A funding round today, promises to change this with sync accuracy as low as 5 nanoseconds with hardware timestamps and hundreds of nanoseconds with software timestamps.

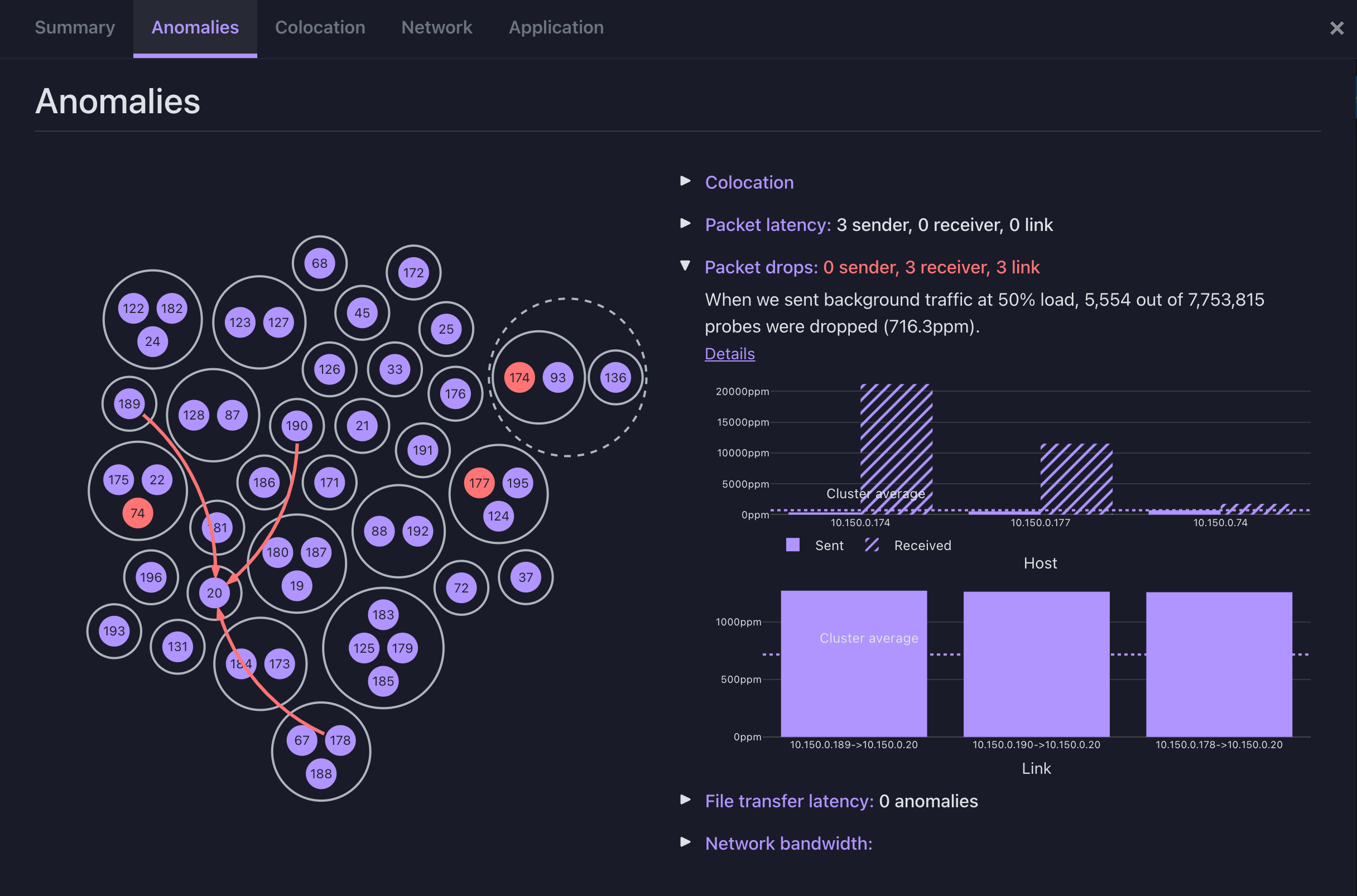

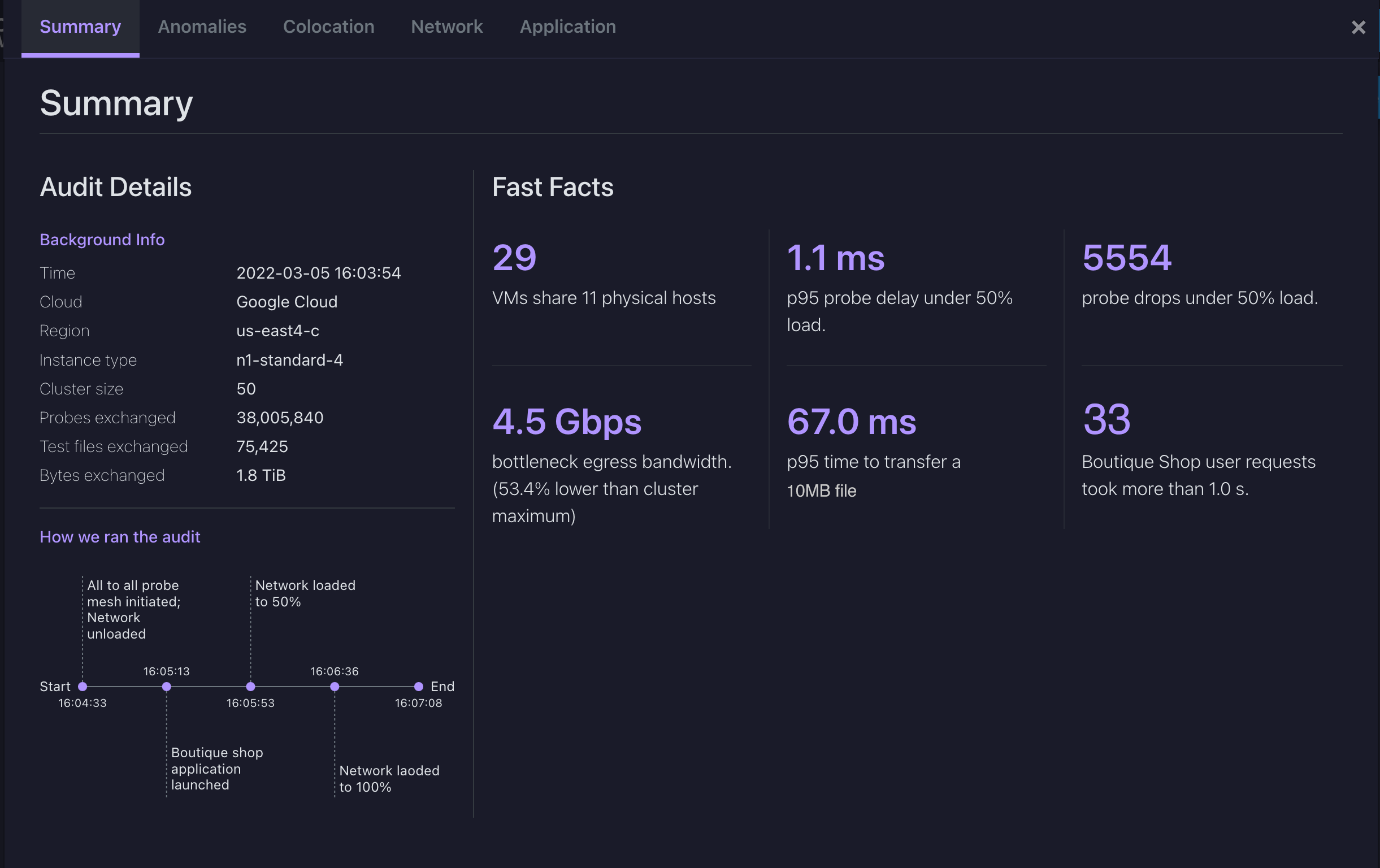

Based on this work, the company is also launching its first product today, Latency Sensei, which can give its users extremely fine-grained latency data in their cloud, on-premises and hybrid environments, which they can then use to find bottlenecks and tune their networks. The company’s customers already include the likes of Nasdaq, Wells Fargo and RBC.

The startup was founded by Yilong Geng, Deepak Merugu and Stanford’s “VMware Founders Professor of Computer Science” Balaji Prabhakar, with VMware co-founder and Stanford computer science professor Mendel Rosenblum serving as board member and chief scientist. Given this group’s pedigree, it’s no surprise that the core research behind Clockwork’s system is based on fundamental academic research the team did at Stanford.

The Network Time Synchronization Protocol (NTP), which is the standard format that most computers use for synching clocks today, is ubiquitous but not very accurate. There has been some work on improving that, with Facebook, for example, contributing a hardware solution to the Open Compute Project last year, but the Clockwork team promises far greater accuracy.

“Sometimes, inside data centers, I couldn’t get them to agree on a second. My phone and the base station here probably agree on the second. Then you get finer and finer and finer — down to the microseconds and nanoseconds. That is very hard. It’s very hard for two clocks to know exactly what nanosecond they are in,” Prabhakar explained. He noted that it’s also not good enough to synchronize these clocks once. You also have to keep them in sync. You can put high-accuracy clocks that are immune to temperature variations and vibration into a server, but that clock would quickly become more expensive than the server itself.

To solve this issue, the team built a system and machine learning model that allows it to very accurately measure the time it takes for a timestamp to arrive at a given server. That’s not so different from how NTP works, but the team then takes this a few steps further by looking at a variety of timestamps and then getting both the offset of the clock and the relative frequency difference. All of this then feeds into the machine learning model. In addition, the team also built the system so the different clocks can talk to each other and detect (and correct) when they are not synchronized.

In the absence of trustworthy timestamps, distributed systems have long had to rely on clockless designs, which adds an extra level of complexity to building complex systems. The Clockwork team hopes that its work will allow researchers to experiment with new time-based algorithms across a number of problem areas like database consistency, event ordering, consensus protocols and ledgers.

The original research by Rosenblum’s and Prabhakar’s team was all about what you could do if you could trust the clocks in a distributed system.

“Currently, nobody uses time except for maybe Spanner at Google, CockroachDB or someone doing database things,” Rosenblum said. “We believe that there’s a lot more places, especially as more and more time-critical things came up. We can do time sync, since we figured out how to do that pretty well. And so we asked: is this part of a trend where we’re going to start programming these systems differently? And [researchers] got kind of excited about that possibility of us being able to pull this off.”

So with the synchronization issues solved, the Clockwork team is now looking to build products on top of this, starting with Latency Sensei. But Prabhakar also noted that the team is already working on another project that makes it easier to detect congestion inside of data centers. TCP, he noted, is great for wide-area networks, but inside the data center, it is quite wasteful. But when you know more about the network — and its latencies — then that in turn could be used to provide the TCP protocol with better hints about how to best route packets inside the data center.

The company’s Series A round was led by NEA, with participation from well-known angel investors, including MIPS co-founder John Hennessey, early Google investor Ram Shriram and Yahoo co-founder Jerry Yang.