Mozilla has added an official translation tool to Firefox that doesn’t rely on cloud processing to do its work, instead performing the machine learning–based process right on your own computer. It’s a huge step forward for a popular service tied strongly to giants like Google and Microsoft.

The translation tool, called Firefox Translations, can be added to your browser here. It will need to download some resources the first time it translates a language, and presumably it may download improved models if needed, but the actual translation work is done by your computer, not in a data center a couple hundred miles away.

This is important not because many people need to translate in their browsers while offline — like a screen door for a submarine, it’s not really a use case that makes sense — but because the goal is to reduce end reliance on cloud providers with ulterior motives for a task that no longer requires their resources.

It’s the result of the E.U.-funded Project Bergamot, which saw Mozilla collaborating with several universities on a set of machine learning tools that would make offline translation possible. Normally this kind of work is done by GPU clusters in data centers, where large language models (gigabytes in size and with billions of parameters) would be deployed to translate a user’s query.

But while the cloud-based tools of Google and Microsoft (not to mention DeepL and other upstart competitors) are accurate and (due to having near-unlimited computing power) quick, there’s a fundamental privacy and security risk to sending your data to a third party to be analyzed and sent back. For some this risk is acceptable, while others would prefer not to involve internet ad giants if they don’t have to.

If I Google Translate the menu at the tapas place, will I start being targeted for sausage promotions? More importantly, if someone is translating immigration or medical papers with known device ID and location, will ICE come knocking? Doing it all offline makes sense for anyone at all worried about the privacy implications of using a cloud provider for translation, whatever the situation.

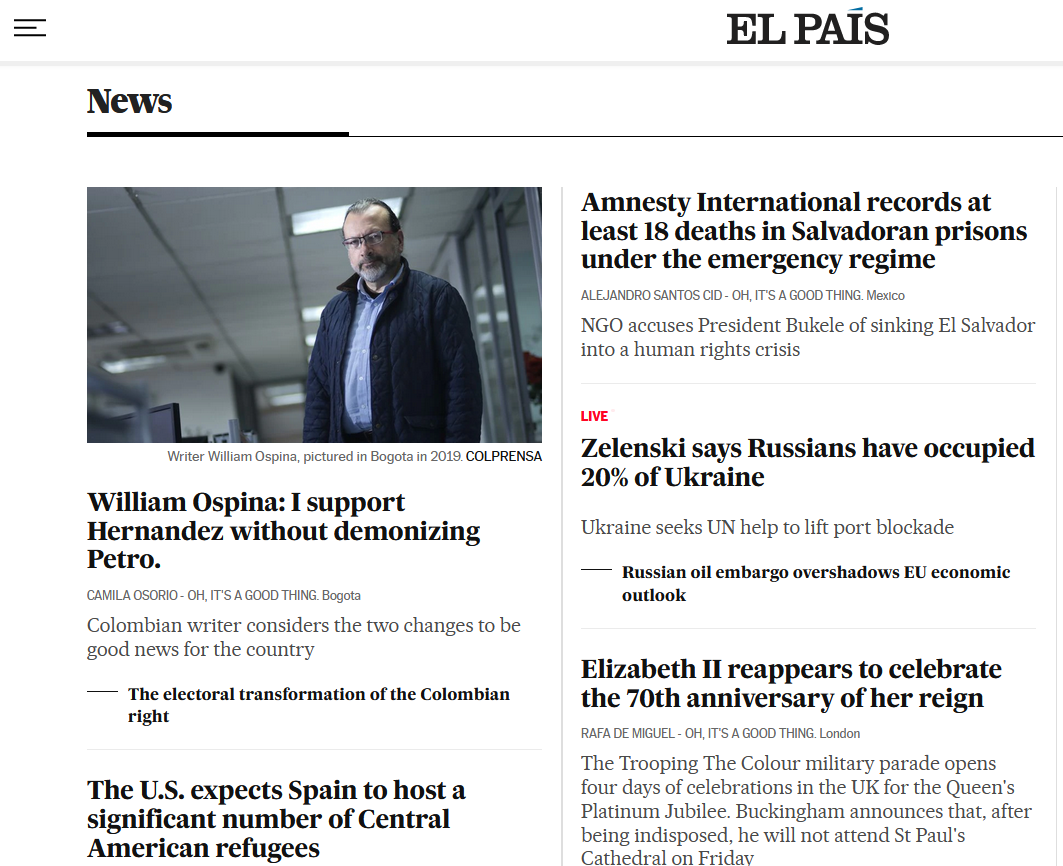

I quickly tested out the translation quality and found it more than adequate. Here’s a piece of the front page of the Spanish language news outlet El País:

Image Credits: El País

Pretty good! Of course, it translated El País as “The Paris” in the tab title, and there were plenty of other questionable phrasings (though it did translate every | as “Oh, it’s a good thing” — rather hilarious). But very little of that got in the way of understanding the gist.

And ultimately that’s what most machine translation is meant to do: report basic meaning. For any kind of nuance or subtlety, even a large language model may not be able to replicate idiom, so an actual bilingual person is your best bet.

The main limitation is probably a lack of languages. Google Translate supports over a hundred — Firefox Translations does an even dozen: Spanish, Bulgarian, Czech, Estonian, German, Icelandic, Italian, Norwegian Bokmal and Nynorsk, Persian, Portuguese and Russian. That leaves out quite a bit, but remember this is just the first release of a project by a nonprofit and a group of academics — not a marquee product from a multi-billion-dollar globe-spanning internet empire.

In fact, the creators are actively soliciting help by exposing a training pipeline to let “enthusiasts” train new models. And they are also soliciting feedback to improve the existing models. This is a usable product, but not a finished one by a long shot!