In February 2019, Reggie Fils-Aimé announced that he would be leaving Nintendo after 16 years — 13 of which were spent as the president and COO of the company’s North American division. It was a fruitful run, filled with more ups (Wii, Switch) than downs (Wii U) during a time of tremendous growth for the gaming industry.

A lifelong serial executive, Fils-Aimé has retired from that aspect of the industry, while still maintaining a presence in gaming. He sat on GameStop’s board (later resigning in 2021), joined investment and consulting firm Brentwood Growth Partners, and even briefly hosted a gaming podcast (as one does during a global pandemic).

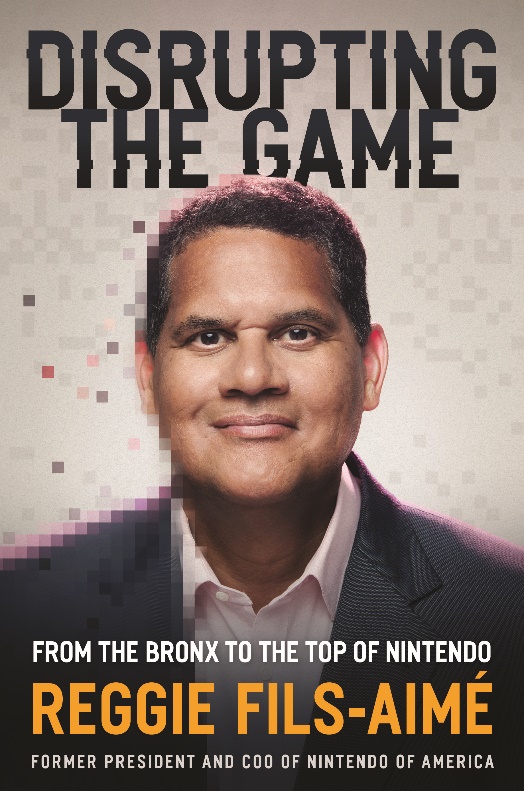

Earlier this month, he released the book “Disrupting the Game“, which charts his journey from the Bronx to the Nintendo boardrooms. We caught up with Fils-Aimé to discuss his time at Nintendo, plans for a $200 million SPAC and where he sees gaming headed.

I was going to ask how retirement is going, but “retirement” may be too strong a word.

My form of retirement is doing things that I like, with people I like doing them with. So whether it’s board service, whether it’s the SPAC that I’m involved in, whether it’s been writing and launching the book, it’s my form of retirement, and I’m having a lot of fun.

What are the plans for the SPAC?

The SPAC is in the broad digital entertainment space. We went public in December of last year. We were oversubscribed by about a billion dollars, so we went public. $230 million is our war chest. But with a billion dollars left on the table, it means we can go after a fairly large acquisition and take it public through the SPAC process. We’ve got until September of next year to identify our target and execute the transaction. We’re in the process of meeting with a lot of different companies and a lot of potential players.

Image Credits: Brian Heater

What trends in gaming are you specifically most excited about?

I do believe that web3 is going to create some opportunities. In particular, I think blockchain could lead to some unique types of digital entertainment. I also believe that the creator economy has unique opportunities. Everyone wants to be a creator. These tools and companies that are leveraging this have an opportunity to do quite well. Another thing I would highlight is that, while there have been a number of large acquisitions in the gaming space, I do believe that’s going to give rise to new, independent companies, led by creators who just don’t want to be part of these larger organizations.

Three companies have dominated the console space for so long. Do you see room for another player?

I do. There are a number of companies that are approaching the creation of that next platform in new and unique ways. Look at what Valve is doing on the PC side. You’ve got Steam and Steam Deck. What they’re trying to do is create a portable experience for largely PC-type games. That could grow to be a separate platform, potentially. I think what Epic is doing is very interesting. Obviously, you’ve got Unreal, that’s become a foundation for game developers. Unreal now is also being used by animators and people in the film industry. That can become a different type of platform. Unity is playing in the same space, though I think they’re a little bit further behind. I do think that there is room for other platforms, but they’ll be defined differently than, say, a Sony, Microsoft, Nintendo.

Are you bullish on AR and VR?

I’m very bullish on AR. I think that AR leads to more communal-type of experiences, and there are already proof points as to what AR gaming can be. I am not sold from a gaming perspective on VR. I think VR has some very interesting business applications, but I haven’t yet seen a great gaming experience in VR. One of the lessons from Virtual Boy is not letting the hardware fully dictate the content. Obviously that pre-dates you, but there were struggles with the Wii U, as well.

Absolutely. Nintendo has heeded that message, more times than not, and I think more times than any other older platform. Their mentality has always been, it’s got to be about the games, it’s got to be about the gameplay. Their developers always want to bring unique forms of gameplay. And that’s what drives the tech to bring it to life. It’s always got to be in the games.

Image Credits: HarperCollins Leadership

From the outside, there were frustrations covering the company, including the speed with which it embraced technologies like smartphones. Nintendo seemed to be dragging its heels. You arrived as an outsider. Did you experience similar frustrations inside the company?

Myself and my team embraced the role of educating the developers in Kyoto around what were key trends to be thoughtful about, to be aware of how the industry was shaping up. The fact is, you need to communicate these forward-looking pathways constantly. And you need to repeat yourself constantly, in order to get traction. But once the company would really believe in a direction and come up with a unique approach, then typically, they would break through with incredible successes.

Is Nintendo more nimble — or at least more open — than when you started?

I do believe that’s true. I think a lot of that started with Satoru Iwata. He very much embraced new and different ideas. And I think he certainly drove the company in that direction. The company has always had a history of innovation and a history of doing things quite uniquely. But under his leadership, there was an embrace of taking risks and moving forward aggressively. And I do believe that continues today.

One of the things I appreciate about the book is the discussion around relative failures. It’s safe to say the Wii U wasn’t the success you were hoping for. What lessons did you take away from the experience?

The game pad, as an innovation, did not deliver in the way we hoped. The company really believed it would allow different types of gameplay maybe best exemplified by Nintendo Land. In the end, the company was not able to deliver on that proposition. The second thing I would highlight was the pace of content was not sufficient in order to maintain momentum. For the launch, the games came out way too slow. The third piece I would highlight was that we still utilized predominantly internal development software that was not easy for external developers to utilize, and therefore to create content for the system, which further exacerbated the lack of content, because the first party wasn’t able to deliver the games on time.

Those were some very harsh lessons that we’ve positively applied to the Nintendo Switch. The core proposition of the Switch, that you could play on your big screen TV and then undock the platform, take it with you, is a core proposition that resonated for the player.

What are those conversations like behind the scenes, when it’s clear to you that it’s time to sort of cut your losses and move on to the next thing?

The conversations are incredibly tough. The fact of the matter is, there’s not always agreement. I pushed incredibly hard, as an example, to try and get the complete proposition down to $99. I was convinced if we could do that, we would have sold another 50 million units of hardware for the Wii and an associated level of software. But unfortunately, the economics of the system didn’t allow that to happen.

For the Wii U, it became clear after we’d already done a price decline — after we’d already used traditional tactics, skill bundles and color changes — the platform still was not performing to our expectations. It was an incredibly tough conversation with the key developers in the Kyoto headquarters to begin working on the next system and begin thinking about what that would be. But also, back at Nintendo of America, to keep focus on engaging with the retailers, keeping focus on launching some key pieces of software to maintain some semblance of momentum.

Image Credits: Nintendo

Looking back on your time at Nintendo in writing this book, are there any major regrets?

I look back at moments, key decisions, and acknowledge that the end decision didn’t go the way I wanted. The pricing decision for the Nintendo 3DS is a classic example from my Nintendo days. I was convinced that launching at $249 was not going to go well and argued to the best of my ability to launch at a $199 price point. In the end, Mr. Iwata had the ultimate decision, and he said “no.” Within months, we had to do a massive price decline down to $169. I believe if we had launched at a $199 price point, we would have been successful from the start. But what do you learn from that? How do you, in the future, be more effective in selling that type of controversial decision?

You seem to enjoy the flexibility this new life has afforded, but if the right opportunity came along, would you consider taking an executive role again?

You never say never. But I don’t believe so. Right after I retired, I was approached to lead a significant organization. Like any smart person, you evaluate it, but in the end, I decided that running a large business isn’t something that today excites me. What excites me is making a trip to the Bronx, and spending time with young people and sharing my story and encouraging them, to follow their passions and to live their dreams. What excites me is writing the book, and sharing my principles. What excites me is being in the boardroom and sharing my experiences with other senior leaders to help them grow and manage their business more effectively. Those are things that I can’t do at the scale I’m doing now as an executive.

We talked a bit about the SPAC. It could be that as we find a private company, and look to take them public, that I may need to play a role with that company, maybe be chair of the board or some other type of role. Certainly if that comes to pass, it’ll be something that I’ll consider and do. But my mindset right now is to share my experiences and to encourage and empower that next generation of business leaders.