Luis Severino cupped the glove around his ear in frustration. The Yankee Stadium two-strike Death Star siren was blaring over the PA, the announcers reasoned. The pitcher signaled frustration with a new piece of technology that’s quickly been rolled out on baseball’s biggest stage. Manager Aaron Boone walked out to the mound, handing Severino a replacement piece.

It was a brief, embarrassing moment for PitchCom, a new piece of hardware that’s quickly made its way onto the uniforms of pitchers and catchers across MLB. After a season of testing in the Low-A West minor league, there was one major issue its creators haven’t addressed: user error.

“I left it in the dugout,” Severino confessed to reporters after the team’s 4-2 win over Boston.

“We were worried about that,” says PitchCom co-founder, Craig Filicetti. “Honestly, it is so lightweight and so imperceptible. We’ve had people that just walk away with them, when they’re on their head in several situations.”

It was a momentary — and understandable — moment of forgetfulness for a pitcher in the middle of his first starting game since 2019. It was funny enough in hindsight that even Severino had to laugh, and ultimately didn’t tarnish what has thus far been a wildly successful debut for a new technology in a sport that’s often been outwardly hostile to change.

PitchCom won nearly universal acclaim in MLB this week, from traditionalist White Sox manager Tony LaRussa to orthodoxy-busting starter Zack Greinke, who fried baseball fans’ collective brains by yelling out pitches in a 2020 game against the Giants.

Of course, for all of the feet dragging we’ve come to expect from MLB, there are certain aspects of the game the league is eager to change, from a ballooning pace of play (the average game ran 3 hours, 10 minutes during the 2021 regular season) to sign stealing. The latter came to a head in 2019, when former Houston Astros pitcher Mike Fiers revealed that the 2017 World Champion team had concocted a system of video cameras and trash-can beating to let their batters know what the opposing pitcher would be throwing.

The scandal was the primary catalyst behind PitchCom’s founding.

“I thought about it for a while, and figured there must be a way to provide signs covertly,” co-founder John Hankins tells TechCrunch. “Baseball has been trying to solve this issue for a while. They’ve had a number of people come in with a lot of different methods to prevent sign stealing. They had buzzers, but counting nine buzzes is going to slow the game down to a crawl, especially if someone shakes it off.”

Image Credits: PitchCom

Hankins, a lifelong baseball fan, found inspiration closer to home. Fellow self-described mentalist Filicetti had created a wrist-based system for sending cues onstage. An electrical engineering major in college, Filicetti says the Live Show Control device has been utilized by thousands across 60 countries.

“Jumping off the technology that Craig had already done,” Hankins adds, “I thought, why don’t we use a push-button transmitter that we can put on the catcher’s wrist and have it play to the player’s hat, rather than an ear piece, so they don’t lose situational awareness.”

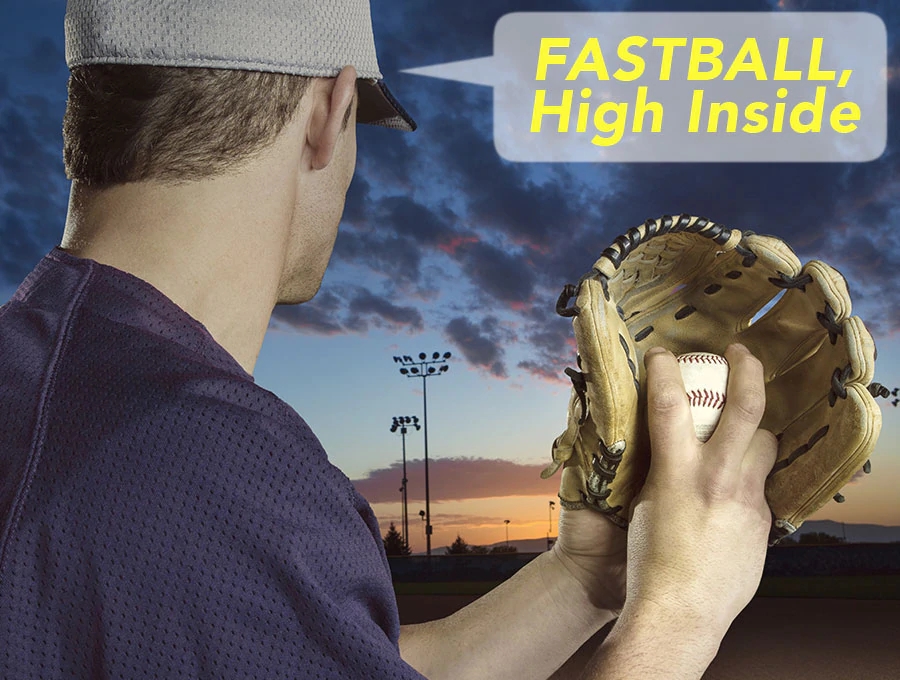

The final product hues closely to the pair’s original vision. The catcher wears an input device on his inner-forearm that sports rows of buttons. The teams assign each a different pitch and can add location. When the combination is pressed, it’s transmitted to the earpiece, sending the pitcher instructions like, “Slider, high, inside.” On the outside of the wrist piece is a printed cheat sheet, though the pair say many teams are opting to do without it, as the catchers memorize combinations. In addition to customizing button combinations, teams and players can also input custom voices. “They can put in their grandmothers,” says Hankins. “They can put in their coach’s voice.”

The product utilizes an encrypted wireless protocol to avoid high-tech sign stealing. If, say, a piece is lost, the team can re-encrypt the system to circumvent foul play. An early iteration of the earpiece relied on bone conduction, though ultimately PitchCom determined that the volume simply wouldn’t be loud enough to compete with the sounds of a full stadium. Beyond the early minor league testing and spring training, it’s been difficult to mimic a live game setting. In a sense, the players themselves are doing the testing in a high-leverage situation in front of a national audience.

There are on-field limitations, as well. MLB has only authorized its use for defensive purposes, including pitching and picking off baserunners. That means batters and the baserunners themselves won’t be able to use it on-field. Questions remain; for example, whether the product will be able to compete with the noise levels of packed crowds during the playoffs.

“It’s difficult to test for,” says Filicetti. “We’ve been trying to gather how many dBs of noise you’ve got on the mound. But I will say — and MLB agrees with this — that these opening nights are a pretty good representation about what they’re gonna get during finals. And we’ve seen very good success. We have headroom and things to play with. We have volume control and places we can go. We’re monitoring this closely.”

The company was bootstrapped by Hankins and Filicetti and founded on a major gamble. It was a product developed for one customer: the biggest baseball league in the world.

“It was very much a risk build,” says Hankins. “There was one customer only, and we had no feedback when we were initially building. Would players like it? We didn’t know any players. The league wasn’t in contact. I tried contacting reporters, I called MLB Radio and they quickly dismissed me. I tried to get local reporters who were reporting on the sign-stealing scandal. Eventually we got connected with someone who had a connection to the Players Union and Major League Baseball.”

Roadblocks persisted. The timing of the first prototype — March 2020 — couldn’t have been worse. The league was scrambling to put on a season of baseball amid a global pandemic, ultimately reducing 162 regular season games down to 60.

Image Credits: PitchCom

“We did get [MLB’s] attention at the end of 2020,” Hankins adds, “during the playoffs. In San Diego, we met with their executives, put a prototype on their head and they loved it. From there, it’s been great. We met with them a few times virtually and they asked if we could send them some for spring training 2021 for them to test. We couldn’t go in there because of COVID protocols, so they had MLB people take it in to seven different spring training camps and show them. The response was very good.”

This year’s season got off to its own rocky start, as negotiations between MLB and the Player’s Union threatened to post-postpone — or even cancel — the season. Ultimately, a compromise was reached. The delayed 2022 season kicked off last week, and with it, a number of teams hit the field sporting PitchCom devices.

The public reaction was immediate. Some traditionalists still balk at the introduction of a new on-field technology, though most of the feedback has been positive — particularly with regard to speeding up the pace of play. PitchCom’s founders say they’ve been fielding requests from international and minor leagues, along with a spike in interest from women’s professional softball teams. Currently, the team is still focused on providing the best experience for MLB’s 30 teams, but the question of scaling is top of mind.

“Scaling is going to be a challenge,” says Filicetti. “We have to keep our number one customer happy.”