On a clear afternoon, Laxmi (name changed) was sitting in her office in Gujarat, India, when she received a message from her distant relative, saying that they received some of her “morphed” nude photos from multiple phone numbers on WhatsApp along with a text that reads, “loan thief.”

“I was numbed and clueless,” she said.

It was the first time the 32-year-old customer service executive was informed about the circulation of her roughly edited photos after taking her mugshots from the government ID she had initially submitted to get credit from a mobile loan app called Fast Coin.

However, before that particular call, she received scores of threatening and abusive phone calls and messages from men who identified themselves as loan recovery agents.

All this started just a week after she applied for a small loan of around $100 that she needed due to a severe financial crisis earlier this year.

Laxmi turned to a startup loan platform rather than a bank for many of the same reasons others do: she did not have the minimum salary typically needed for banks and other financial institutions in India typically to disburse loans; and upstarts generally not only require less vetting but their turnaround times are faster, and she needed to get the money in a single day to pay for her house rent. So instead of going to a bank, she chose to get the loan from Fast Coin, an app her office colleague suggested.

She had repaid the loan within a couple of weeks of getting her salary the following month, but she claims that in the following months, she paid a further $630 over and above the original loan amount to get rid of abusive calls and messages. Yet the threats have continued.

Apps offering instant loans have grown since the emergence of the coronavirus pandemic, with hundreds of millions of dollars so far disbursed through them.

Fueled by a nationwide lockdown, India has been in the midst of a wider economic downturn. Unemployment in the country hit 23.52% of its total labor force in April 2020, per data shared by the Mumbai-based economic think-tank Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). Those numbers are going in the right direction now: the rate dipped to 6.80% in July this year from the 6.96% reported in the same month last year and the 7.40% in July 2020, but they are all still rates higher than the U.S., U.K. and China, and point to why these loan apps get the traction they do.

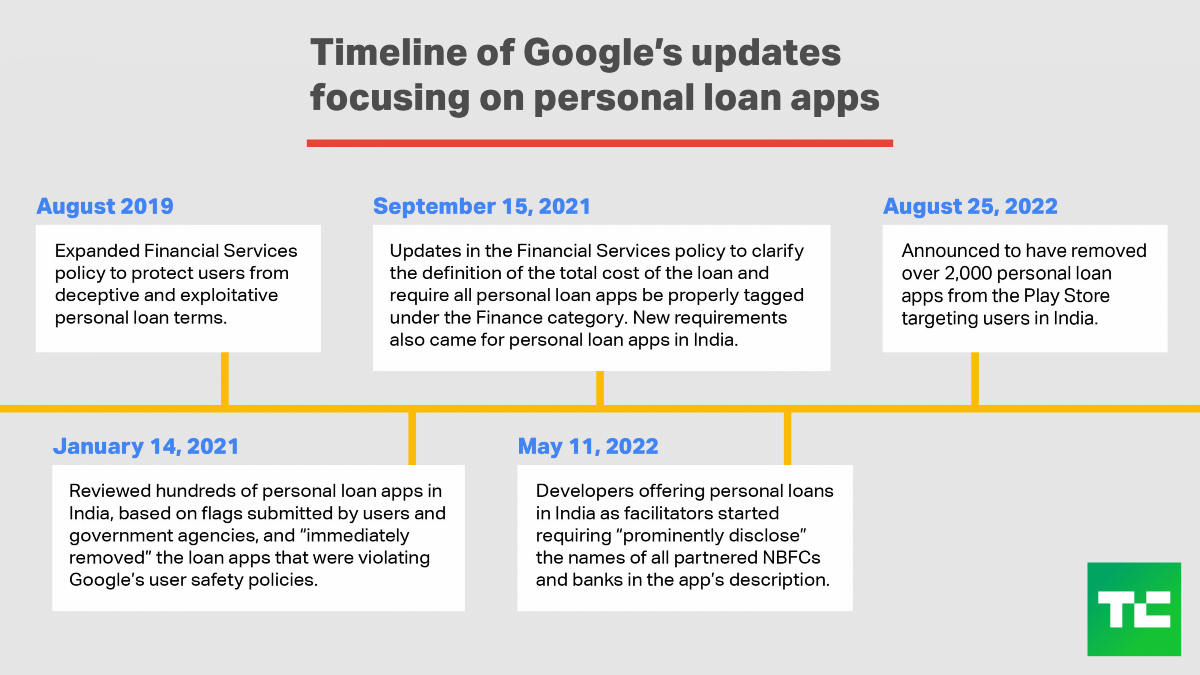

Various stakeholders including the government and Google have been taking action against some of the most egregious loan apps in order to limit their impact in late 2020 and 2021. Law enforcement agencies in the country are also taking some efforts to raise awareness.

Image Credits: TechCrunch/Bryce Durbin

Nonetheless, it remains an ongoing problem. As Google pointed out this week, it’s pulled more than 2,000 dodgy loan platforms apps from its Play Store in this year alone. But the problem is that people who have had the misfortune of using them are still facing abuse and harassment in the aftermath of their engagements.

Some are reportedly even taking their lives due to the immense pressure they get from these loan apps’ unregulated agents. According to local news reports, nearly two dozen suicide cases owing to harassment coming from loan app operators have been reported online. More than half a dozen of them were reported specifically from Hyderabad — a major tech center in the country, and in fact home to Google’s largest campus in the country.

Hyderabad cybercrime police officer KVM Prasad told TechCrunch that since January, the state’s law enforcement agency has registered 134 cases and made 10 arrests related to loan apps. He also said that the police identified 314 suspicious loan apps. The agency sent its list Google, he said, but few were deleted. Many of them are still available on the Play Store, he said, and their ranks are still growing.

“These loan apps are emerging like anything this year,” Prasad said in an interview with TechCrunch.

He claimed that many of the apps were the same that Google initially pulled on request from the government in late 2020. The operators didn’t disappear, though. Lazarus-style, they simply changed the names of their apps and carried on, contacting the old customers and disbursing loans on accounts without getting prior consent, and subsequently harassing users to repay, he said. (We have asked the agency to provide examples of apps that have been taken down but now are operating again under a different name, and we will update this as we learn more.)

Since January, the Hyderabad police have identified 250 billion transactions through these loan apps. Each of these transactions was between $25–250, the police officer noted.

An investigation by India’s anti-money laundering agency has separately found that loans of over $500 million were disbursed by these apps, according to a report by The Economic Times.

Like the Hyderabad police, TechCrunch has learned that the Fintech Association of Consumer Empowerment (FACE) shared a list of loan apps with Google to get them pulled from the Play Store. Other state police departments and nodal agencies including the Enforcement Directorate are also investigating issues with loan apps and raising their concerns with Google.

The Android maker told TechCrunch that it did take action against some loan apps without disclosing any specifics.

“We have reviewed hundreds of personal loan apps in India for compliance with the relevant policy, based on flags submitted by users and government agencies,” a Google spokesperson said in a prepared statement emailed to TechCrunch. “For apps that remain non-compliant past the deadline, as is done for any policy non-compliance, we have been taking necessary enforcement action as part of our ongoing policy compliance sweeps, including removal of apps from the Play Store.”

Last year, Google revised its Play Store developer program policy for financial services apps with additional requirements for loan apps in India, including the requirement to submit a copy of the license for review in case the developer is licensed by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) for providing personal loans.

Since May, developers who are not registered by the central bank are also required to “prominently disclose” the name of all the registered Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs) and banks that are giving loans through their apps. Google also made it mandatory for developers to ensure that their account name matches the name of the associated registered business name provided in their declaration.

“We will continue to assist the law enforcement agencies in their investigation of this issue,” the spokesperson said.

Who needs a backdoor when you have a front door?

Predatory loan providers, however, are operating on a number of levels to do their dirty work.

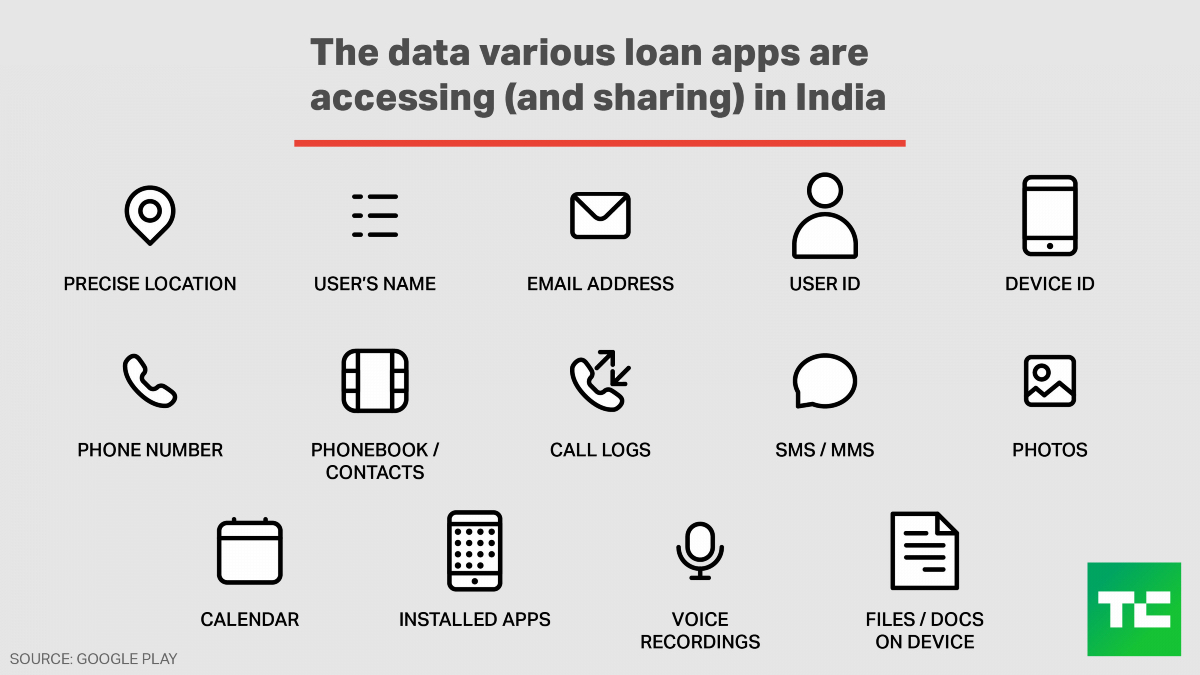

First, they gain user data access, including users’ contacts and call records, which they use for recovery and harassing people. In some cases, the operators of these apps get user consent by pretending to use their contacts in case they are not reachable. Some apps, however, take all that data without getting any prior consent from users. A few apps also claim that they need access to contacts and call records for fraud prevention. Nevertheless, the actual purpose in most cases is to use the phone numbers obtained for recovery purposes, which sometimes become too harsh to bear.

Image Credits: TechCrunch/Bryce Durbin

Second, they’re using channels like established app stores to connect with users. In the case of the Google Play Store, for example, ordinary consumers assume using an app available there is credible enough because of the vetting Google does before approving them to be listed.

“For a layperson, it is very difficult even to figure out whether the RBI has authorized a particular app,” said Shehnaz Ahmed, a senior resident fellow and fintech lead at independent think-tank Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy.

The prevalence of dodgy apps on the Play Store is a longstanding issue, of course, not limited to predatory loan apps in India. In the case of the latter, Google has enlisted the help of users themselves, who are directed to report non-compliance of its developer program policy to alert Google, which in turn “take[s] appropriate actions” against those developers.

But Srikanth Lakshmanan, a coordinator at consumer awareness collective Cashless Consumer, who closely reviewed a list of loan apps impacting people in South India, believes that Google is not being held as accountable as it should be for the situation.

“Google does not want anyone else to say that they’re also failing,” he said.

In January last year, the RBI constituted a working group on digital lending to get a clearer picture of the issues with loan apps in the country. The group found nearly 600 illegal loan apps that were available across a list of Android app stores, including the Play Store.

Rahul Sasi, co-founder of cybersecurity firm CloudSEK, who worked with the RBI’s group for identifying questionable loan apps, said that flagging such apps was difficult even for Google. The current systems are trained to flag malicious apps with, say, malware in them; but not apps that can harm after some time of their installation, not just by way of malware but through the malicious actions of people connected to those apps’ services.

It’s tricky to know where to draw the line in some cases, and it raises big questions over what kind of data access any app should be allowed to have by default, lest it get abused.

“It’s like Facebook,” he said. “In that case, [you could claim it’s] also a bad company [since] it has access to all the data on your phone.”

Saikat Mitra, senior director and head of Trust and Safety at Google Asia-Pacific, also acknowledged while talking to reporters at the company’s event this week that using only machine learning algorithms to flag such apps doesn’t work.

“We can even go to the extent of reverse engineering code and look into that,” the executive said. “But you have to understand the problem of loan apps compared to other apps basically is what we call ‘offline bad,’ which means the all the various [violations are] happening outside of the app, they’re not happening on the app.”

In the last few weeks, the RBI has considered some working group recommendations to toughen rules for digital lending in the country. Experts, however, believe that much work is still needed.

“What the RBI seems to be doing is going after the regulated entities to look at certain kinds of digital transactions… many other entities are operating in the market, which perhaps are currently under the RBI’s radar because of how the regulatory structure is organized,” said Ahmed.

Issues with legitimate players

Several loan apps that are not registered with the RBI or are not using a financial partner enrolled by the central bank are available in the market to target people looking for instant credit. However, this does not mean that the ones that appear legitimate and are registered with the RBI are doing fair business.

Lakshmanan of Cashless Consumer told TechCrunch that some well-funded startups operating in the digital lending space also indulge “in all sorts of shady practices” and harass people taking loans from their apps.

User reviews on the Play Store and Apple’s App Store suggest the same scenario as hundreds of abuse- and harassment-related complaints exist against many apps that are considered legal in the country.

TechCrunch shared the details of these apps with both Google and Apple to get their comments. Google did not give any direct response on the matter, and Apple did not respond to the request for comment.

Earlier this month, the RBI issued a circular to advise regulated lending platforms to have fair methods and practices related to loan recovery agents and “should not resort to intimidation or harassment” of their borrowers.

Gaurav Chopra, president of Digital Lenders Association of India (DLAI) and founder of IndiaLends, told TechCrunch that the announcement made by the RBI was to reiterate the guidelines and make sure that everybody is aware of them. He also claimed that the adverse effects of loan apps had declined.

“I would say we are at probably less than 10% of what we saw two years back,” he said.

The DLAI has over 80 members on its board, including some of the widely used digital lending platforms.

Associations including DLAI and FACE are looking for a self-regulatory organization (SRO) to address consumer grievances on behalf of their members.

“At the end of the day, the RBI, while very robust, cannot deal with every single complaint in the most timely manner,” Chopra said while referring to the requirement of establishing an SRO.

However, market experts like Ahmed of Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy do not look for an SRO coming from the industry. They instead want the RBI to set up a grievance mechanism.

Adam J. Aviv, an associate processor of computer science at the George Washington University, said that even though Google and Apple have deployed privacy labels on their app stores, both companies seemed to have no priorities to use them to communicate risks involved with loan apps or to restrict their privacy-violating behavior.

“Both Google and Apple do place some restrictions on apps in other contexts, such as for children-focused apps or health apps, to comply with local laws and regulations. Similar policies could be put in place by governments for mobile loan apps. This might force the hand of the mobile app stores and the developers to meet minimum privacy standards for data collection requirements and uses of that data,” Aviv said.

Similar predatory loan app patterns in other developing markets

Just like India, people in countries including Mexico and Kenya are also facing abuse and harassment instances through loan apps. Experts believe that it is due to lax regulation.

Collins W. Munyendo, a graduate research assistant at the George Washington University who conducted research in loan apps impacting users in Kenya, said that developing countries are a ready-made market for perpetrators targeting money-seeking individuals.

He pointed out that unlike the U.S. and U.K. where people primarily have a credit history and a centralized way of generating credit scores, a similar system lacks in developing markets to a large extent. Some measures including new legislation, though, did take place particularly in Kenya in the last few months to limit the circulation of such apps.

“Anyone could literally wake up and create one of these apps and put them out there because the regulatory framework just doesn’t exist yet to control that space,” he said.