Microsoft has linked the exploitation of several Windows and Adobe zero-days targeting organizations in Europe and Central America to a little-known Austrian spyware maker.

The technology giant’s threat intelligence and security response units have linked a number of cyberattacks to a threat actor it calls “Knotweed,” better known as the Vienna-based intelligence-gathering company, Decision Supporting Information Research Forensic, or DSIRF. On its website, DSIRF says it was founded in 2016 but claims to have over two decades of experience delivering “data-driven intelligence to multinational corporations in the technology, retail, energy and financial sectors,” as well as offering red team testing, where hackers are given permission to find and exploit security vulnerabilities during product testing.

Microsoft said in its report out Wednesday that Knotweed has been active since at least 2020 and developed spyware — dubbed Subzero — that allows its customers to remotely and silently break into a victim’s computer, phone, network infrastructure and internet-connected devices. Subzero is similar to NSO Group’s Pegasus and Candiru’s DevilsTongue spyware in functionality, and is often used by governments to monitor journalists, activists, and human rights defenders.

According to a copy of an internal presentation published by Netzpolitik in 2021, DSIRF advertises Subzero as a “next generation cyber warfare” tool that can take full control of a target’s PC, steal passwords, and reveal its real-time location. The report claims that DSIRF, which reportedly has links to the Russian government, advertised its tool for use during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. The report states that Germany was also considering the purchase and use of Subzero for use by its police and intelligence services.

Microsoft notes that as well as selling the Subzero malware, DSIRF — a.k.a. Knotweed — was observed using its own infrastructure in some of the attacks, suggesting more direct involvement in the targeting of victims, which included law firms, banks, and strategic consultancies with known victims in Austria, Panama, and the United Kingdom.

But the technology giant said it has confirmed with a victim targeted by Subzero that they had “not commissioned any red teaming or penetration testing,” and that the activity was unauthorized and malicious.

Subzero is distributed through a number of vectors, according to the report, including multiple zero-day exploits in Windows and Adobe. This includes the recently patched CVE-2022-22047 flaw, a bug in the Windows client-server runtime subsystem (CSRSS) , which can be used to obtain a higher level of access to the victim’s device than the logged-in user. Microsoft said it had patched at least four zero-days used by DSIRF since 2021.

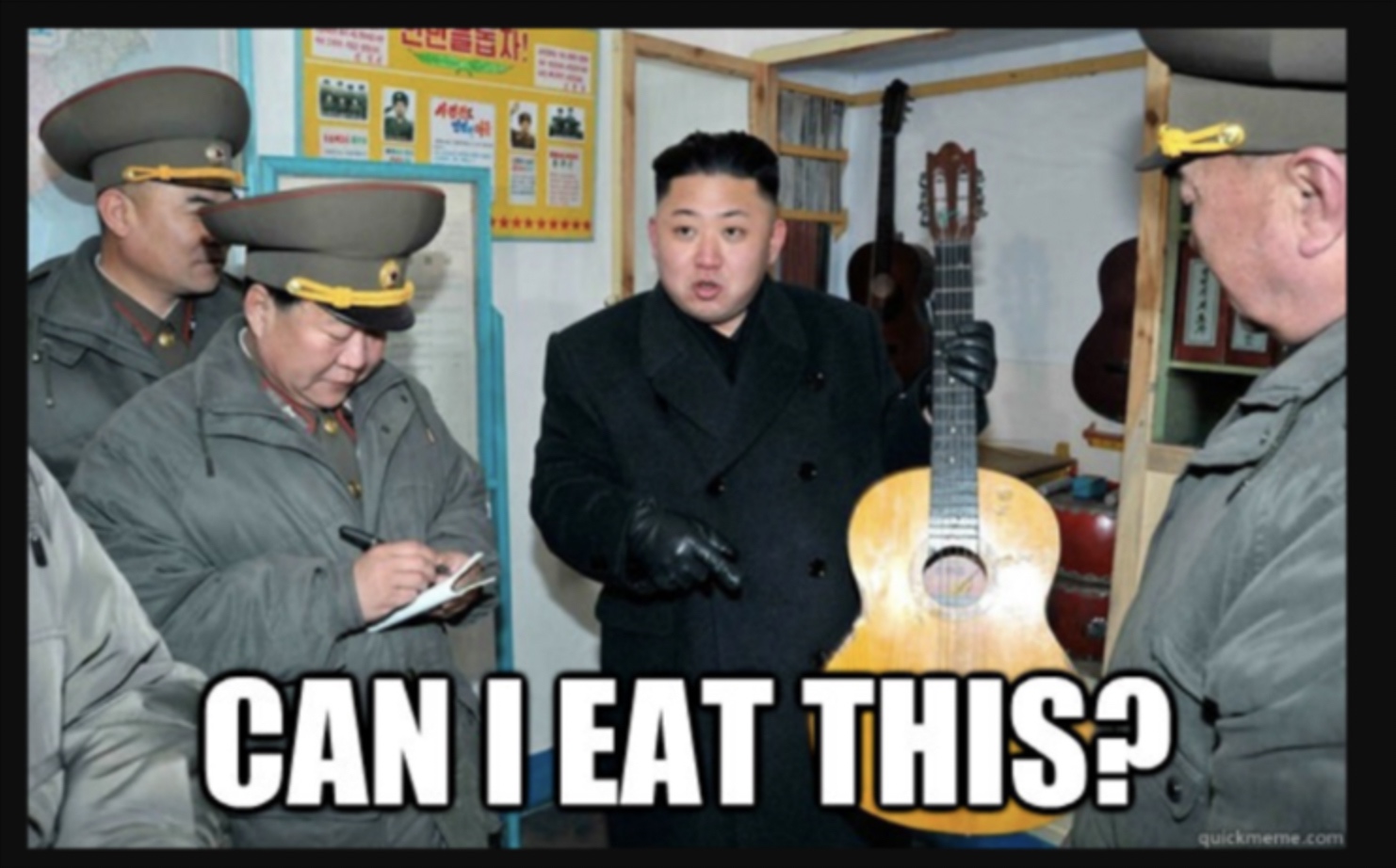

Knotweed also embedded malicious macros in Excel documents, which included second-stage malware hidden inside a regular-looking but “abnormally large” JPEG image that was disguised as a meme. Macros are a common way for malicious actors to gain access to deploy malware and ransomware, but were recently blocked by Microsoft in Office apps by default.

This “abnormally large” JPEG is disguised as second-stage malware that pulls the main spyware binary from the attackers’ command and control servers. Image Credits: Microsoft

When reached by phone, a DSIRF representative said they would provide TechCrunch with a response to Microsoft’s report, but the response was not provided by press time.

To defend against these attacks, Microsoft recommends that organizations patch CVE-2022-22047, keep antivirus software up to date, and enable multi-factor authentication.

The tech giant is also calling for more action to be taken against spyware makers, warning that DSIRF will not be the last cyber mercenary to come to light.

“We are increasingly seeing [private-sector offensive actors] selling their tools to authoritarian governments that act inconsistently with the rule of law and human rights norms, where they are used to target human rights advocates, journalists, dissidents and others involved in civil society,” said Chris Goodwin, general manager at Microsoft’s Digital Security Unit. “We welcome Congress’s focus on the risks and abuses we all collectively face from the unscrupulous use of surveillance technologies and encourage regulation to limit their use both here in the United States and elsewhere around the world.”